The Child Miners of Floristella

The terrible story that lies at the heart of one of the most productive sulfur mines in all of Sicily

The most solemn of our visits to date in Sicily has been to the Parco Minerario Floristella Grottacalda. We couldn’t have imagined the secrets hidden beneath the grandeur of the Palazzo Pennisi, the mansion on the hilltop overlooking the mining operation where the owner and his family lived. Its architecture is grand, and reminiscent of southern plantation estates, where formerly enslaved people toiled all their lives. It is a harsh, poignant reminder of the oppression, abuse and subjugation the wealthy have relied upon throughout history to make themselves richer.

Sulfur’s history in Sicily dates back to 900 BC. It is believed that the native people of Sicily, the Sicanians, Sicels and Elymians, exported it to Greece and North Africa. Its use in gunpowder made it very popular in the 1700s, especially to the French and British. By the time of the industrial revolution in the 19th century, 90 % of all the sulfur in the world came from Sicily.

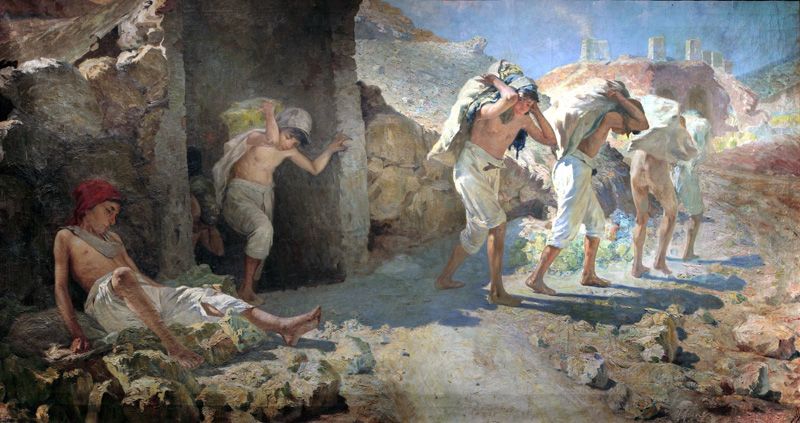

This valuable resource led to the recruitment of more than 32,000 miners, where they toiled all their lives. The mines were deep and narrow which led to the use of small children as a main labor source. Their parents, so poor they could not feed the children they had, traded them as ‘indentured servants.’ They were known as “i carusi,” the Sicilian language word for a small child.

I carusi rarely saw the light of day; entering in the morning and not leaving until the evening. The heat in these mines was 45°C/113°F and 100% humidity, which meant they labored naked, often with only a leather strap covering their genitals. The terrible working conditions led them to develop weak and lopsided bodies with deformed knees from carrying excessive loads. Partial or complete loss of vision was not uncommon. Not to mention the deadly accidents that occurred and took the lives of innocent mineworkers.

The mining activities produced hydrogen sulfide gas, a poison, to which the workers were constantly exposed. This made it difficult to breathe and caused many health issues which shortened their lifespans significantly. A miner was not expected to live beyond 40 years old. It was once referred to as brimstone and thought to be smoke from the fires of hell.

Historians document Sulfur mining as a sad chapter in Sicily’s history, and yet others argue that the activity promoted the growth of Sicilian economy and propelled it to greater heights through preservation of its political prominence in an age that was characterized by military actions and the industrial revolution. But evidence points to, as has been repeated throughout history, that a select few benefited financially through the exploitation of those who were far less fortunate, illiterate, and oppressed.

Today, the site of Floristella is preserved as an open air museum and UNESCO has certified it as a World Heritage Site. The Mining Park represents one of the most important industrial archeological sites existing in Southern Italy and one of the largest, oldest and most significant sulfur mining areas in Sicily. Sulfur mining activity is documented from the end of the 1700s to 1986, when all activities linked to sulfur production ceased definitively in the area.

In fact, the tunnels, structures, equipment and systems used for the extraction of sulfur in the two centuries of activity of the mine are still visible. From the ancient access shafts to the underground tunnels to the three extraction wells to the smelting ovens, to the Gill furnaces; to the ruins of the service buildings built near the wells that included an infirmary, lodgings for the miners, and the after-work area for the workers; from the railway section between the stations of Floristella and Grottacalda through which the sulfur was loaded and shipped, to the internal railway network for the transport of the wagons with the mineral. These artifacts are physical evidence of the harsh reality that existed at Floristella.

Booker T. Washington, the prominent African American leader, himself a formerly enslaved person, visited the sulfur mines of Sicily at the turn of the 20th century as part of a larger visit to Europe to research the social conditions there. In his resulting work, The Man Farthest Down, he expresses his horror and shock:

"I am not prepared just now to say to what extent I believe in a physical hell in the next world, but a sulfur mine in Sicily is about the nearest thing to hell that I expect to see in this life."

As an eyewitness, he described the plight of i carusi as follows:

“From this slavery there is no hope of freedom, because neither the parents nor the child will ever have sufficient money to repay the original loan. [...] These boy slaves were frequently beaten and pinched, in order to wring from their overburdened bodies the last drop of strength they had in them. When beatings did not suffice, it was the custom to singe the calves of their legs with lanterns to put them again on their feet. If they sought to escape from this slavery in flight, they were captured and beaten, sometimes even killed”

The sobering visit to Floristella is a reminder that appearances, more often than not, aren’t accurate. The mansion on the hill is beautiful, but hidden beneath its splendor are the horrors that afforded the landlord and his family its lavish lifestyle. With all the beauty that surrounds us daily in Sicily, we feel it’s important to know it more deeply, and appreciate the reasons for the massive emigration of its poorest people after the second world war.

Here's a short video from our visit:

The Floristella story

Show your love & support

As an independent, reader-funded operation, I rely on the backing of readers willing and able to financially support work of this nature. Behind my desk there is just me, seeking to prove in any way that I can, unencumbered by shareholders or billionaire owners, that it is possible to cut through the bullshit of what we're taught about life and find the means to live longer, better, with less, wherever we are.Your support makes all the difference! If my writing here seems to be living up to those intentions or otherwise enriches your own life in any way, please consider supporting it one of these two ways:

♲ Invite a Friend: Don't toss it away, recycle and share what you read here with others you know who might like to read it too. Email, Facebook, LinkedIn, wherever else you fancy spending your online social time, every mention helps!

☯︎ Be Yin to My Yang: Most of what you'll read here is free, it's everything else that costs money. Become a paid subscriber for as little as $5 per month, or make a one-time donation in any amount, to help me bring balance between the two.

Keen on the Bitcoin? No problem. Shovel a bit (or two) my way: bc1qn56cg3htqq77zm4y06900m0u05xpy57zxkkmz9